Single-cell RNA sequencing has revolutionized how we study biology. A single experiment can profile hundreds of thousands of individual cells, revealing the diversity of cell types in any tissue. But there’s a bottleneck: someone has to make sense of all that data.

The standard workflow—quality control, filtering, normalization, clustering, and cell type annotation—requires PhD-level expertise and weeks of hands-on work. Data scientists at research institutions are perpetually backlogged. Scientists wait weeks just to see their first annotated UMAP.

I wanted to know: could an AI agent do this work reliably?

The Architecture

The key insight was that AI shouldn’t replace the bioinformatics—it should orchestrate it. I built a multi-agent system using a LangGraph state machine with four specialized components:

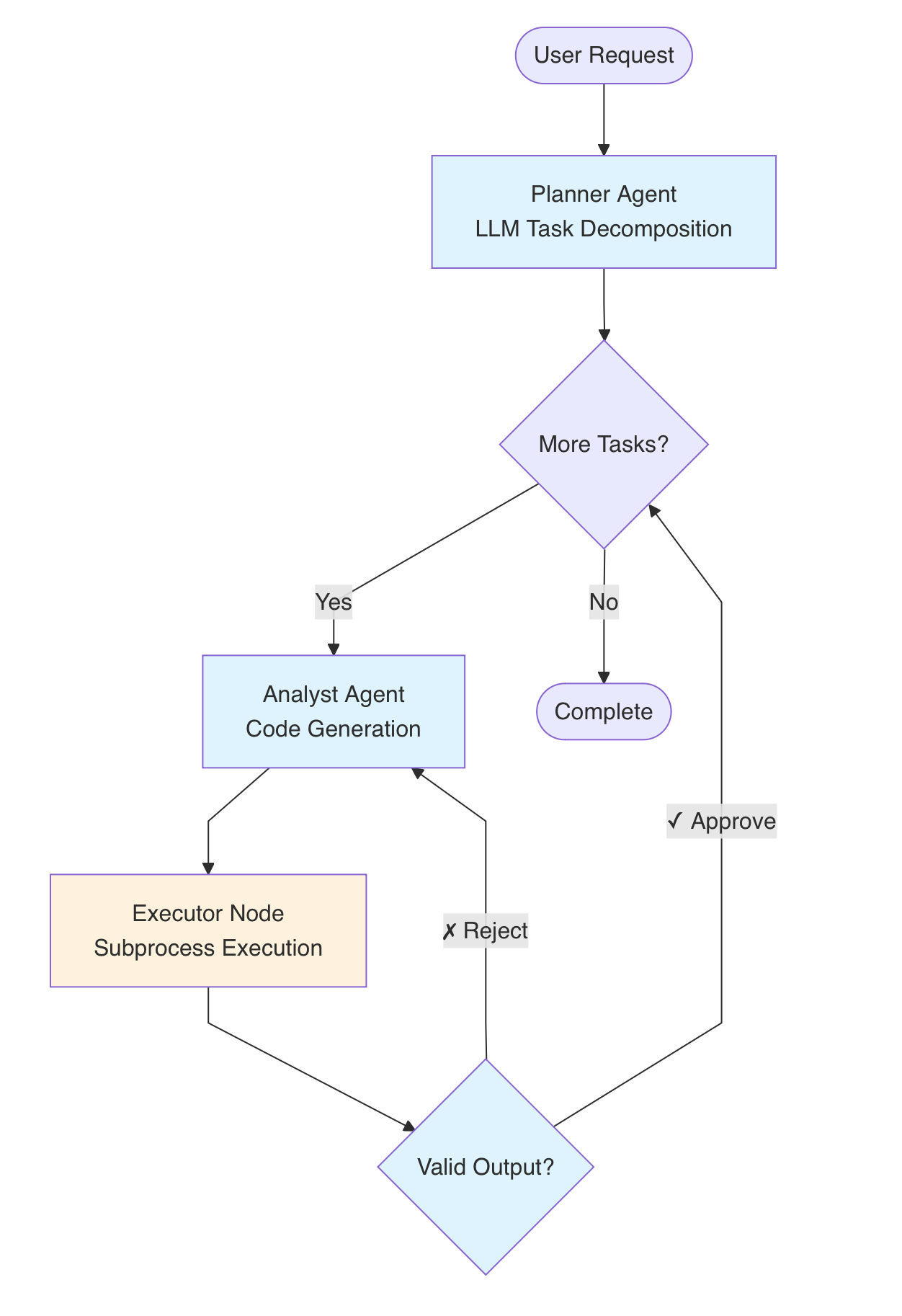

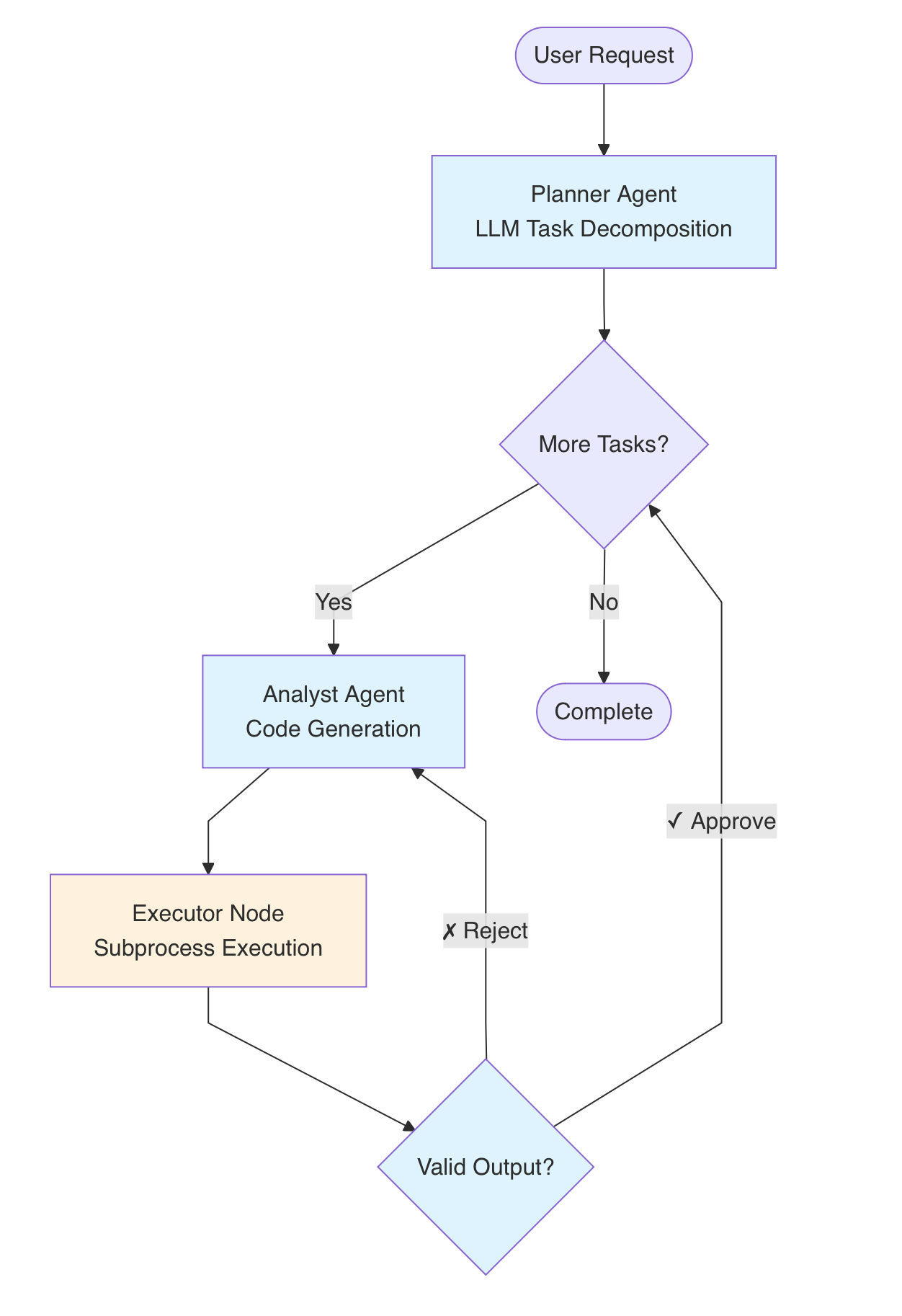

The four-agent architecture. A Planner decomposes high-level goals into tasks. An Analyst generates code using pre-validated bioinformatics “skills.” An Executor runs the code in a sandboxed environment. A Reviewer validates outputs and triggers self-correction loops when needed.

The four-agent architecture. A Planner decomposes high-level goals into tasks. An Analyst generates code using pre-validated bioinformatics “skills.” An Executor runs the code in a sandboxed environment. A Reviewer validates outputs and triggers self-correction loops when needed.

The critical design choice: instead of asking an LLM to “analyze single-cell data” (a recipe for hallucination), I encoded years of best practices into deterministic “skills”—validated code modules for specific tasks like doublet detection, batch correction, or marker gene identification. The LLM decides when and how to apply these skills, but the computation itself is reproducible and auditable.

Evaluation Against Human Experts

The real question isn’t whether the pipeline runs—it’s whether the results are trustworthy. I evaluated the agent against expert human annotations on multiple datasets.

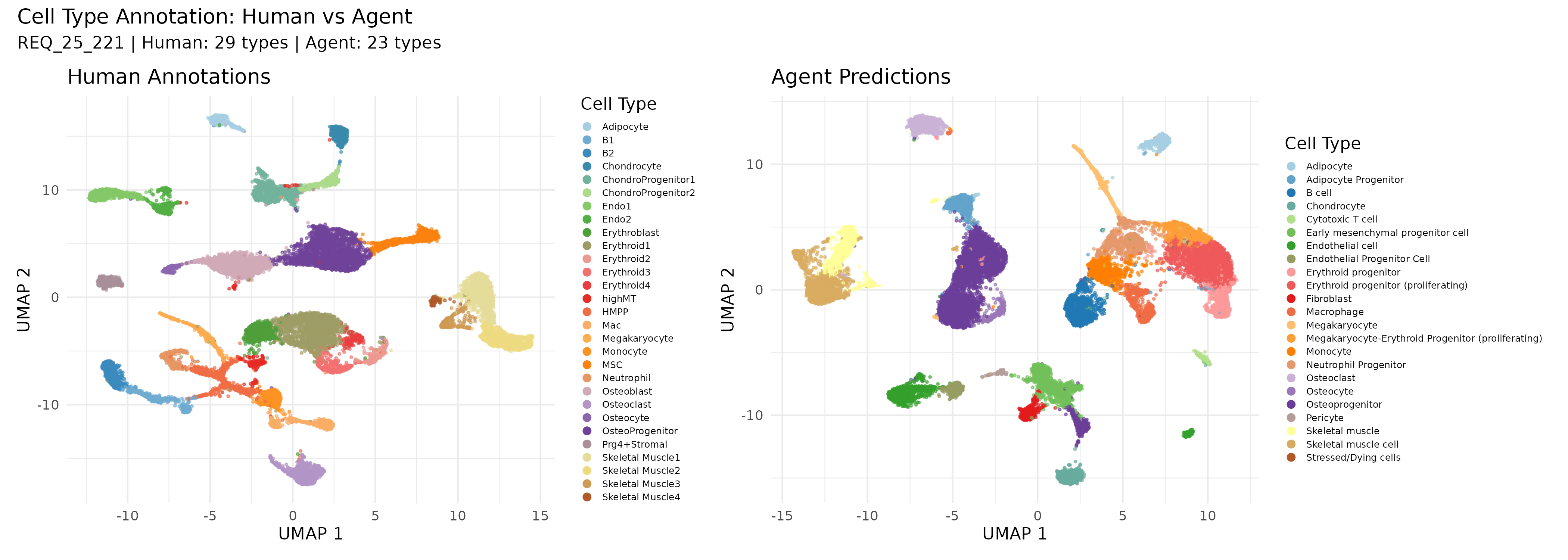

Cell type annotations on a 200,000-cell bone marrow dataset. Left: Human expert annotations (29 cell types). Right: Agent predictions (23 cell types). The agent consolidates some granular subtypes while preserving major biological distinctions.

Cell type annotations on a 200,000-cell bone marrow dataset. Left: Human expert annotations (29 cell types). Right: Agent predictions (23 cell types). The agent consolidates some granular subtypes while preserving major biological distinctions.

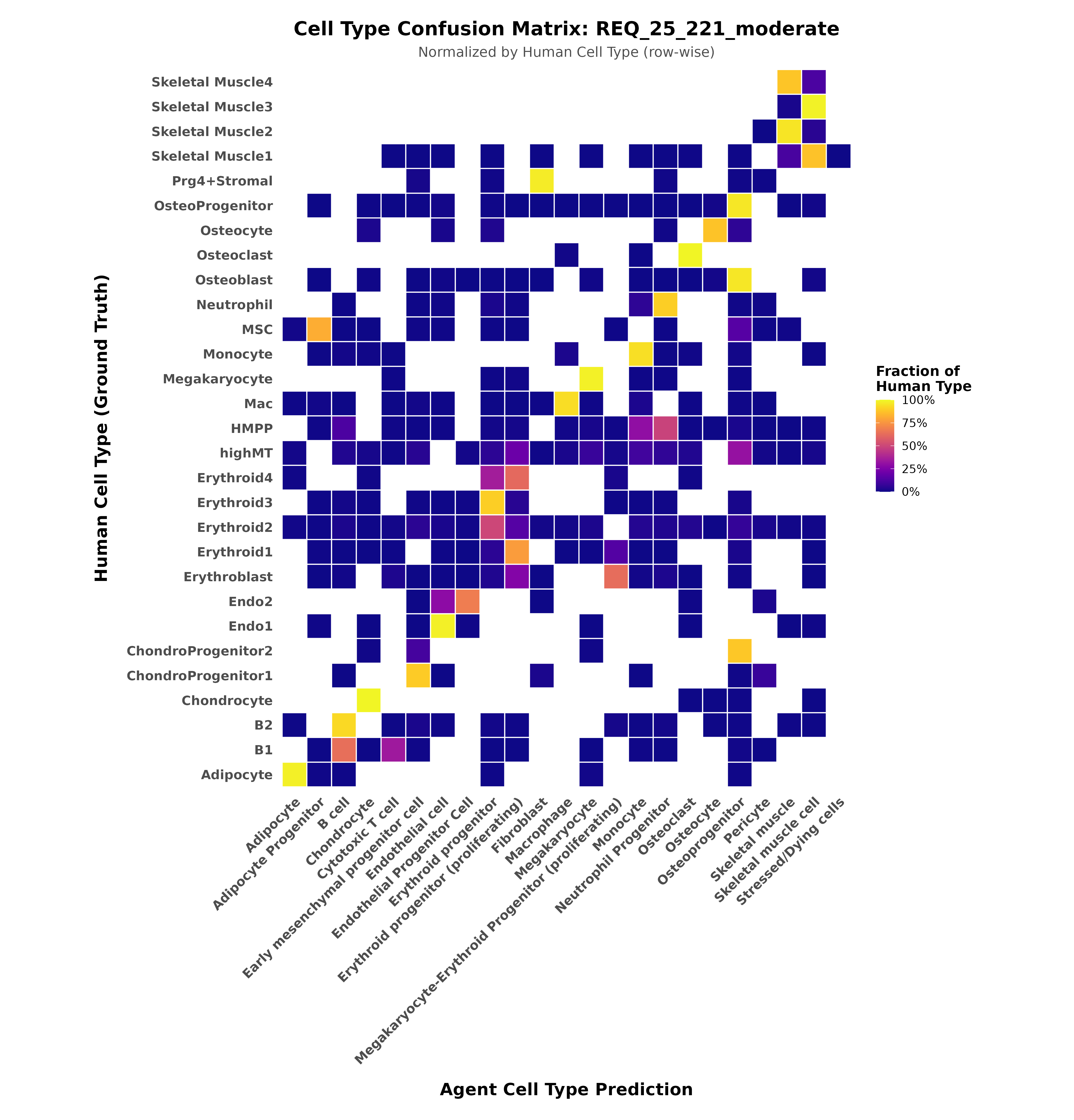

The agent achieved 0.81 Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) against human expert labels—remarkably high agreement for a task that typically requires years of domain expertise. The confusion matrix reveals where the agent struggles: related cell types like erythroid progenitors at different stages, where even human experts often disagree.

Confusion matrix showing agent predictions (x-axis) versus human ground truth (y-axis). Strong diagonal indicates high agreement. Off-diagonal elements reveal biologically meaningful confusion—the agent groups related progenitor populations that humans sometimes split into finer subtypes.

Confusion matrix showing agent predictions (x-axis) versus human ground truth (y-axis). Strong diagonal indicates high agreement. Off-diagonal elements reveal biologically meaningful confusion—the agent groups related progenitor populations that humans sometimes split into finer subtypes.

What This Means

The Director of Genomics at my company reviewed the results and concluded that “the agent version is superior” for certain datasets—not because it’s smarter than humans, but because it applies consistent criteria across all cells without fatigue or batch-to-batch drift in judgment.

More importantly, this converts weeks of PhD-level work into hours. A 300,000-cell dataset processes end-to-end in about two hours, producing a fully annotated h5ad file and an HTML report ready for scientific review.

The framework is generalizable. The same architecture—skills plus LLM orchestration plus self-correction—can extend to other long-horizon computational biology tasks. The key is knowing where AI reasoning adds value and where deterministic computation is non-negotiable.